BoP: The Engineer's Fight in Show Business

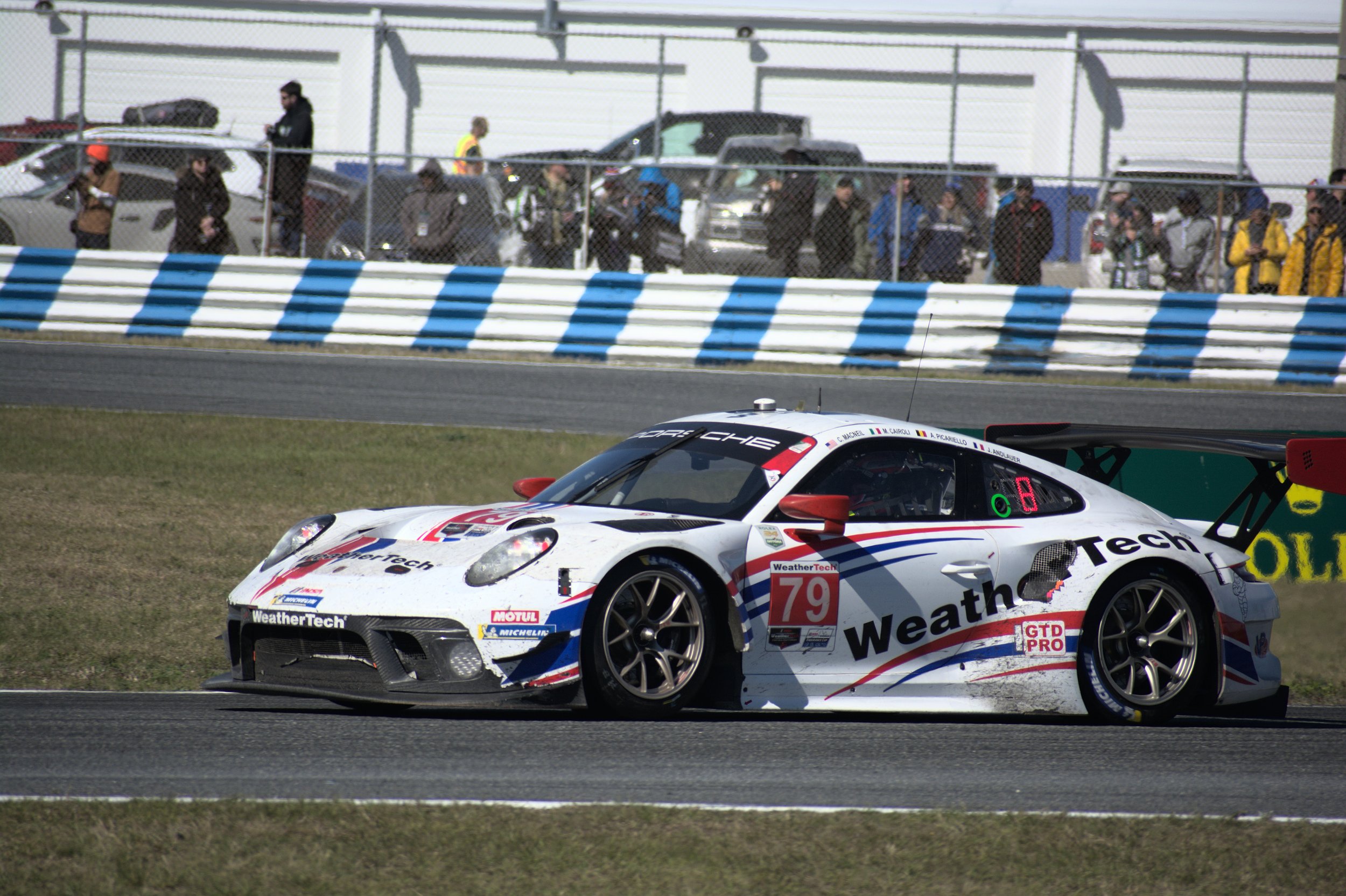

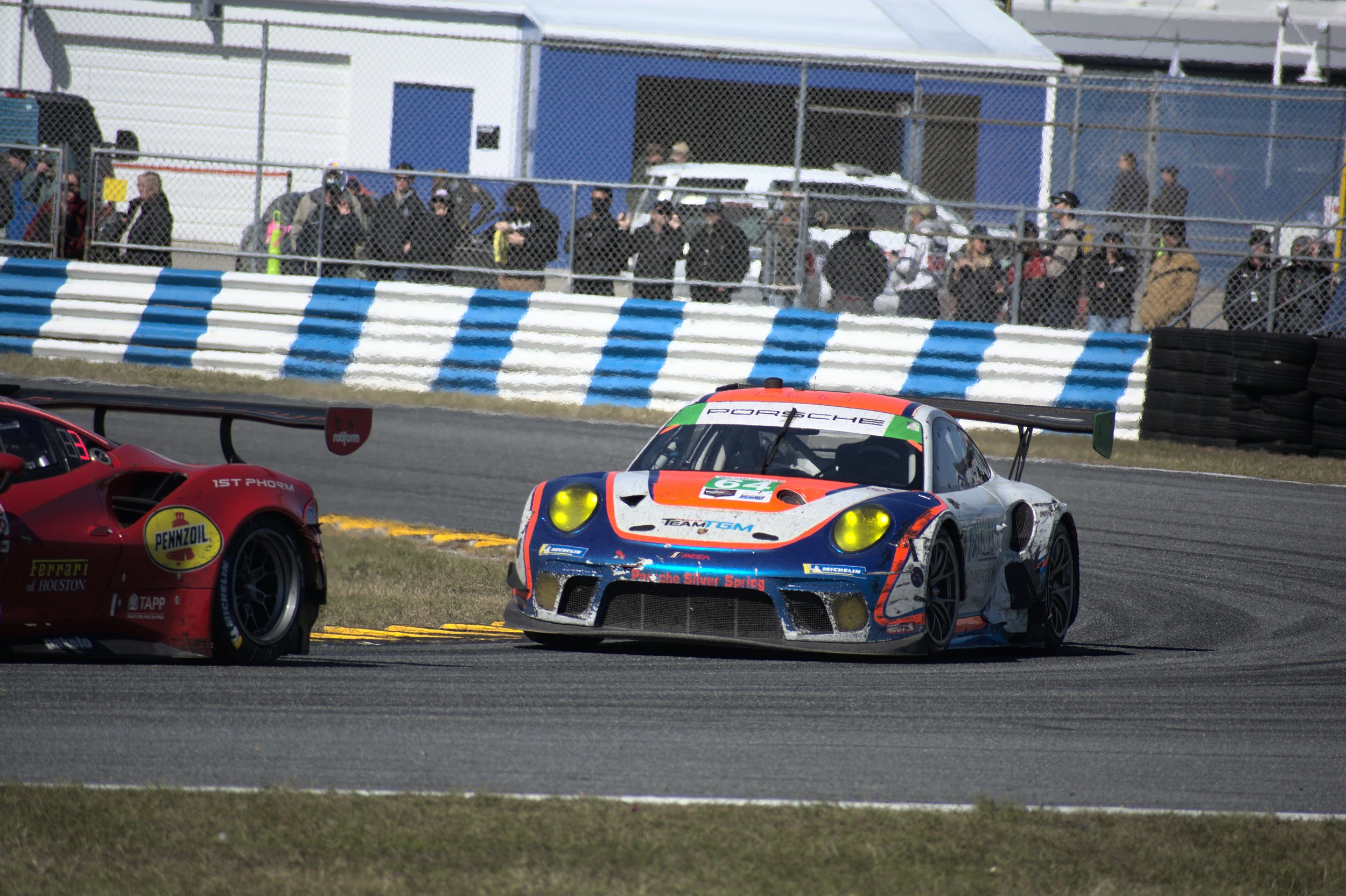

With both Porsche and Ferrari releasing their most up-to-date weapons for GT3, it is the perfect time to discuss one of the most controversial aspects of modern sportscar racing. Anyone that follows motorsport developments closely has at least heard the phrase "balance of Performance" (BoP), and for better or worse, it's here to stay.

The idea for BoP is based on the concept of "success ballast" applied in many GT and Touring Car series since the early 2000s. Success Ballast, as its name implies, is the process of adding weight or ballast to a driver dependent on its success. In Touring categories, this has been applied in different ways, with kilograms of weight added to cars per championship point or after each win, with a maximum ballast capped at a specific weight. It was established to make the championships more driver-focused rather than on the machinery and to limit excessive platform developments, which can lead to a team or manufacturer running off with the tournament. If we place the issue of fairness to the side, teams understand the concept behind the rule and have been playing with clever ways to minimize its effect. Developing creative solutions such as designing the vehicle and setups specifically to a set ballast, thus achieving a better vehicle balance when running ballast, minimizing its effect. Keeping the game of cat and mouse between engineers and regulators alive and well. The idea was even considered for application in Formula 1 and promptly dismissed; a big bullet missed right there

In 2006, things changed with the introduction of GT3 spec machinery. The GT3 class was designed to slot as the third step on the ladder behind the GT1 and GT2 classes by providing a competitive category that would allow a large number of manufacturers to get involved. Manufacturers had to follow a relaxed rulebook where their platform had to be based off a mass production car and comply with specific broad regulations and safety. At this point, you may ask how this would ever work. Wouldn't it lead to insane GT1-level prototypes being utterly unattainable to the masses and with a rampant development curve? There was a big catch; the regulations stipulated the idea of Balance of Performance.

Balance of Performance is a tool to level the performance of very different racing machinery to run in a singular class. BoP is designed to allow manufacturers to join and be competitive even if their concept may seem less outright performance-oriented than others. Rules aimed to create a category of off-the-shelf racing platforms with a mass of around 1300kg and 600hp. The idea caught on, and in a big way, with a total of nine cars receiving homologation by the first event. To this day, we have a total of 52 GT3 Homologated vehicles in the GT3 class; with such a prominent option pool of options, many winning and non-winning vehicle configurations have been approved to compete. The list includes 4-12 cylinders, mid, rear, and front-engined vehicles, and both naturally aspirated and force induction guises. BoP is set to attempt to match the lap times for all the machinery to make a fair playing field where the teams and drivers' ability is the winning factor rather than buying the fastest vehicle. These tuning options by the regulators may include:

Intake restriction

Fuel flow limits

Force induction limitations

Adding ballast

Limiting fuel capacity

Aerodynamics

Tire size

The success of the GT3 didn't go unnoticed by regulators worldwide that wanted to improve racing and guarantee that people that attend or watch the event from their house get the best possible show. GT3 is now one of the most predominant and successful racing categories worldwide, leading to the demise of rulesets with rich histories, such as DTM. The concepts it developed spread all over the motorsport sphere. BoP is now being applied in IMSA, WEC, GT4 class, and many others to guarantee the competitiveness and success of the different series.

Now that we have all the facts over the table, we can discuss why it leaves such a sour taste in the mouths of audiences and engineers alike. At the end of the day, this solution doesn't allow for successful concepts to show their full pace potential. Incredible engineering concepts are hindered to match competitors' performance, which either started with a handicapped platform from the roadcar scene or concepts that look different for the sake of difference…Peugeot, this goes to you.

Engineers are thus changing their approach, deviating from choosing the fastest concepts and performance-oriented design toward what is now known as a "raceable" racecar. This concept encompasses a large number of aspects that affect the structure of how race cars are designed. Platforms are designed with flexibility and use in mind.

This means complex solutions are thrown out for more straightforward solutions that allow for tunability and ease of access. For example, we can look at how Porsche has been and continues to use a naturally aspirated engine on their 911 GT3 racecars; the typical solution for modern racing to extract the most out of a PU is to go the turbocharger route to maximize the efficiency. Porsche decided to go naturally aspirated, more likely to: reduce total part count, reduce service complexity, and costs to a minimum. In addition, for this year's 911 GT3 R, they've increased displacement to 4.2 liters to provide a wider torque band to make it more accessible for drivers and provide functional performance that can be harder to be affected by BoP. Will it hinder their performance compared to forced induction platforms? More than likely, it won't, and their customers will love them for it.

The same thing can be said for the suspension approach they've taken; they've increased the wheelbase to increase stability for amateur drivers and reduce tire degradation, which is another concept that is hard to control with BoP. The aerodynamic concept has also been gone through. They describe that most of the work has been aimed at reducing aero sensitivity, especially pitch orientation, and creating cleaner downforce.

Has BoP limited the outright performance of race classes? Probably, does it make less of an engineering challenge to make a winning car, and engineering a winning team? Absolutely not; the difficulties have just shifted to other areas. There is much more to investigate and discuss regarding BoP, and how it influences modern racing; it is a very controversial topic that can't be condensed into a single article. One thing is for certain engineers will always find an unfair advantage, even in a world where the show trumps the engineering and sporting aspect of our sport.